On the Front Line: How Blockchain Forensics Fight Crypto Crimes

One of the first things that any crypto noob learns about Bitcoin is that it isn’t anonymous. The takedown of dark web marketplace Silk Road is one of cryptocurrencies most-referenced case studies illustrating this fact. It tells how law enforcement bodies can use blockchain forensics to trace the movements of digital money. In this way, they can also uncover the owners of wallet addresses.

But the unmasking of Silk Road’s Ross Ulbricht is only one story. Criminals are continuing to use and abuse cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, for all kinds of nefarious endeavors. Therefore, blockchain forensics provides a few other fascinating tales of attempts to foil the crooks.

Blockchain Forensics in Exchange Hacks

Like Silk Road, the Mt. Gox exchange hack also has its place in the Cryptocurrency Book of Fables (sadly, not a real thing at the time of writing). The story of Mt. Gox has more twists and turns than a corkscrew, and the saga continues to this day. It makes for a fascinating study in blockchain forensics, featuring one hardcore crypto vigilante who spent more than two years of his life trying to uncover who was behind it.

Back in 2014, Swedish software engineer Kim Nilsson was living in Tokyo when the Mt. Gox exchange shut down, and all his Bitcoins suddenly vanished. Later, it would emerge that hackers had been siphoning off funds from the exchange since 2011.

However, in response to the theft of his funds, Nilsson developed a program that could index the Bitcoin blockchain and started investigating Mt. Gox. By searching through each transaction, he identified some patterns. Although by itself this didn’t provide information about who was behind the trades, Nilsson also managed to get ahold of some leaked information about the Mt. Gox database, including a report put together by another developer.

Following the Money

In a painstaking effort that he undertook in addition to his full-time job, Nilsson assembled some two million Bitcoin wallet addresses associated with Mt. Gox. Using a kind of manual brute-force blockchain forensics, he followed the flow of Bitcoins out of these Mt. Gox addresses. He noticed that some Bitcoins stolen from Mt. Gox ended up in wallets that also held Bitcoins stolen from other exchange attacks. By cross-referencing transactions, he found a note attached to a trade that referred to someone called WME.

Through further digging, Nilsson discovered that WME was associated with a crypto exchange based in Moscow. He found that WME held accounts with this exchange, called BTC-e. Nilsson also worked out that some Mt. Gox Bitcoins had ended up in BTC-e accounts.

Unmasking the Villain

Nilsson went online and started trying to find out who was behind the name WME. It was not as difficult as it could have been. Ironically, in a fit of outrage over another exchange having scammed him, WME had inadvertently left his real name on a message board. Nilsson finally discovered the individual behind the Mt. Gox hack: Alexander Vinnik.

Even before Nilsson provided Vinnik’s name to investigators, BTC-e was under investigation due to involvement with various other cryptocurrency criminal activities. By the end of 2016, the US authorities had sufficient evidence to issue a warrant for the arrest of Alexander Vinnik.

However, he was living in Russia at the time, so investigators waited until he left the country for a vacation in Greece. He was apprehended in July 2017 and has been held in custody in Greece ever since. Both Russia and the US have sought to extradite him.

The latest news report stated that the Greek government had approved his extradition to Russia.

While all this sounds like the plot of a movie, it serves to illustrate the degree to which the world of crypto is unregulated. It only took one vigilante using his own blockchain forensics, and years of dedicated focus, to bring down an international cybercriminal.

Professional Blockchain Forensics

Jonathan Levin was also one of the investigators of Mt. Gox, working on behalf of the exchange’s trustees. Levin went on to start Chainalysis, a blockchain forensics company, which provides software that can now undertake the kind of extensive blockchain analysis that Nilsson did by himself.

Blockchain Intelligence Group (BIG) provides a similar service. These companies are used by law enforcement agencies, but also by cryptocurrency businesses who see advantages in using blockchain forensics to screen customers.

Ransomware Attacks

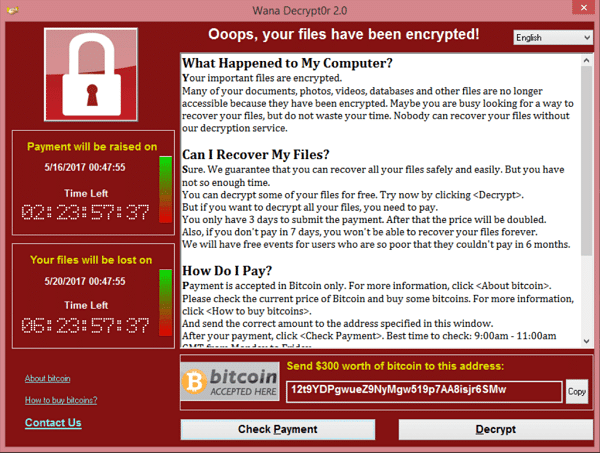

Criminals are now finding other ways of obscuring their movements on the blockchain. Mixer services jumble together coins in an attempt to confuse the trail of individual transactions. Increasingly, criminals, such as those behind the WannaCry ransomware attack, are also using privacy coins such as Monero to increase their chances of remaining hidden.

WannaCry emerged in 2017. It was a global ransomware attack that exploited weaknesses in Microsoft Windows to encrypt all of the data in a users computer. Once the data was encrypted, the program demanded payment in Bitcoin to decrypt the data.

Microsoft quickly released patches, but by that time more than 200,000 computers had been affected across 150 countries. It hit hard. One estimate put economic losses at $4bn.

Although experts advised against paying the Bitcoin ransom demands, the WannaCry attack netted its architects some $140,000 in Bitcoin. The architects remain unidentified.

However, in August 2017, various sources reported movements of Bitcoins from the addresses associated with the attackers. They used Swiss company ShapeShift to convert the coins into Monero, meaning they will now likely never be found given the tight privacy around the use of Monero. ShapeShift has since taken steps to blacklist those addresses.

The Good, the Bad, and the Blockchain

The WannaCry case shows that blockchain forensics, like any branch of forensics, is not infallible. However, like blockchain itself, blockchain forensics is still in its infancy. Of course, criminals will always find ever more creative ways to use cryptocurrencies for nefarious purposes. Hopefully, there will always be someone like Kim Nilsson, or companies like Chainalysis or BIG using blockchain forensics to seek them out.